All About the Great Migration

Every year, the great migration of wildebeest and zebras that takes place in a loop between Tanzania and Kenya begins at the same time from the great plains of southern Serengeti which means “endless plain” in Masai.

Reserves: scenery of the Great Migration of the wildebeest

The Serengeti National Park is the largest park in the country with its 14 750km 2. It forms with the Ngorongoro conservation area an environment of rivers, lakes, forests and plains that is home to approximately 4 million animals and more than 400 species of birds. Almost all the species of the great African fauna are represented, but it is no doubt the wildebeest that totals the greatest number of individuals.

Wildebeest and zebras of the Great Migration

To survive, wildebeest and zebras need plenty of water and pasture every day. As long as the environment offers them, they stay in the same area. But as the dry season begins and resources are dwindling, their survival is at stake, and one of the largest animal migrations in the world begins through the arid savannah.

Gnus can travel up to 70 km per day, but satellite measurements of gnus with collars show a smaller daily average of 4-7 km per day, or an annual average of 1500-2500 km! At the heart of the migration are about 2 million wildebeest and up to 350,000 zebras that move together towards greener grass. It is in a deafening din that cohorts of thousands of individuals gather in the early morning and advance in continuous line in the dust-saturated savannah, Wildebeest rustling and the highly recognizable zebra’s burping.

This gigantic herd is also followed by an impressive number of gazelles, mostly Thomson’s gazelles, which can be estimated at over 250,000 individuals. The mystery of zebras with wildebeest is not yet solved, but it has been noticed that during dry season travel zebras precede wildebeests, while in wet season or once arrived at Masai Mara, they tend to be more close to wildebeest, to mingle with them. This would allow them to better escape the predators who choose to ease of preferentially attacking wildebeest, easier prey than zebras.

The ecological impact of migration is also an important fact in the region. The various actors in the great migration consume about 4000 tonnes of grass in a day, or nearly 1,500 000 tonnes in a year. The "mowing" of grass at the edge practiced by herbivores has beneficial effects for itself. This mowing eliminates competition and favours low-growing grass species, such as those that are often loved by wildebeest. It also prevents the colonization of the savannah by shrubs, especially acacias, and also reduces the risk of fire. Finally, the dung (estimated at 750 tons per day) fertilize the savannah by their nitrogen inputs and the mineral elements of the skeletons of the many animals who lose their lives during this long journey are returned to nourishing land.

The other animals of the Great Migration

This group, a real "walking pantry" does not go unnoticed in the bush. Predators, even if they can follow the herds for a few tens of kilometers, do not migrate. They simply take their dime from the flock that returns every year. The great hunters that are lions, leopards, cheetahs and the few remaining wild dogs are therefore the main actors of this generous buffet.

In the second role we find hyenas, jackals and vultures and in the region of Masai Mara the impressive crocodile of the Nile. Predators are known carnivores, hunters or scavengers and most often both. Indeed, only vultures eat exclusively dead prey and only cheetahs feed only prey they have killed. It should be known that lions and leopards do not hesitate to confiscate a prey killed by a third party unable to defend or to eat a large animal that died of natural causes. Hyenas and sometimes jackals do not just eat carrion or steal other people’s prey, but sometimes hunt and kill for themselves.

The Great Migration through the savannah...

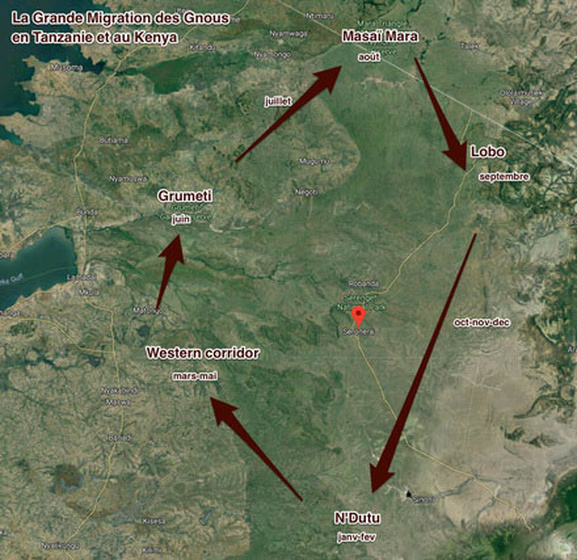

- January to February

From January to February, the herds graze quietly on the greasy grass of the plains of the Ndutu region, not far from the crater of Ngorongoro. January and February are the important periods for these herbivores since they are the two months during which will put bats zebras and wildebeest. The young people will have between one and two months to gain strength before starting their long journey north. During this short dry season, it is possible to participate in the gathering and observe wildlife in the northwest region of Ngorongoro.

- March to May

March to May is the rainy season. March is the beginning of migration. Certainly commanded by one or more female ancestors obeying their instinct, the animals gather and begin to form long daughters of horns and shins across the savannah. The columns first head towards the centre of the Serengeti before heading west.

- In June

In June, the rains are dropping sharply, the animals have joined the "Western corridor" and are heading towards the Grumeti region. The safari season begins in the Serengeti between Seronera and Grumeti.

- In July

In July, the cohort moves north to the Serengeti and the Lobo region, where many camps and lodges allow you to participate in very interesting safaris before reaching the Masai Mara. This magical spectacle also takes on its full dimension, seen from an airplane or during a balloon flight.

- In August

August, we are now in the middle of winter, the migration reached Masai Mara after crossing the famous river of the same name. The crossing of the river is the scene of an intense, raw, sometimes cruel spectacle of wildlife or opposes the determination of one to the voracity of the other. It is in this river that the last actor called the Nile crocodile enters the scene. Nile crocodiles are continuously growing aquatic reptiles that can grow to 6 m long and over, and weigh more than 500 kg. They are capable of long periods of fasting, especially in the dry season when their basic food, namely fish, is buried in the mud. The passage of wildebeest in dry season is therefore the assurance of reserves for days and weeks which should not be deprived. In some places, water flows along easily accessible shorelines. But it is invariably in the same place, dangerously steep by erosion, the ravine being incessant, that the wildebeest, stupidly, want to swim across the river Mara. Usually following a brave or pressed by the mass, they rush in crowds into the boiling water. Slipping, panicking, falling, many die suffocated, crushed, drowned, or even victims of exhaustion, to the great satisfaction of crocodiles, vultures, varans, marabouts wait patiently.

- In October

In October, the dry season, migration begins to descend southwards depending on pasture.

- In November and December

November and December mark the arrival of the short rainy season, when the long cohort descends rapidly towards the south along the eastern edge of Serengeti Park. At the end of December, beginning of January, the loop is closed, and the animals are found in the plains of Ndutu that will be covered with a miraculous green, synonymous with abundant food for the bovids.

Crossing the Masai Mara River

Ecological contribution of death of wildebeest in the Mara River If most wildebeest successfully cross the Mara River in Kenya, a team led by ecologist Amanda Subalusky from the "Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies" questioned the amount of biomass that could represent the many drownings that take place during these crossings. Historical reports and field surveys over several years have estimated the number of drownings at the level of 6200 individuals or about 1100 tons of biomass.

Several thousand tons of carcasses end up at the bottom of the river every year, a real blessing for the local ecosystem. This natural subsidy delivers terrestrial nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon to the river’s food web. Using a method to track nutrients in aquatic ecosystems, the researchers were able to trace nutrients from drowned animals along the food chain. It turns out that each year only a small proportion of the number of dead bodies (about 2%) is eaten by crocodiles, and that 9% would be devoured by several species of vultures, marabouts or other varans. The biggest winners are therefore the fish species present in the river, carcasses representing in fact half of their diet. Once the flesh is devoured and the bones are cleaned, they release even more nutrients into the water, continuing to feed the ecosystem for years to come. It should also be noted that these mass drowning events have little impact on the gnus herds since they represent only 0.5% of the total herd size.

Read more articles:

Discover our safaris.